With time and the currents of the lake, parts of the wreck, such as the ship’s steam boiler, became scattered. On June 8, 2001, this boiler was able to be returned to the main wreck site, thanks to the efforts of the Erickson family of Bayfield, Wis.; the State Historical Society of Wisconsin; and the Great Lakes Shipwreck Preservation Society (GLSPS).

However, the boiler shifted away from the Pretoria’s main wreck site again and had to be returned once more in 2016. Jack Decker, a prominent member of the GLSPS, was the co-project leader of the team that pulled the boiler back again and pinned it to the lake bottom.

Decker’s first trip out there in 2016 when they were working on moving the boiler back was to simply make sure they knew where it was and get some other details because they weren’t quite sure how big the boiler was.

Although they had pored over books and historical documents, they still couldn’t find anything that actually said how large the boiler was. They were guessing it would be around 7,000 or maybe 9,000 pounds. Since Decker and his team had never been to the dive site, they wanted to take a look at it and see where they thought they could place it so that it wouldn’t be moved around again.

“We did a lot of diving that first time,” described Decker, “but we ran out of time for that weekend, so then we came back with everything we thought we needed to lift the boiler and move it into place.”

When Decker and his team went back to lift it, they put two 2,000-pound lift bags and a 6,000-pound lift bag on it, giving them a total of 10,000 pounds of lift. But it still wouldn’t budge. Luckily, they happened to have brought an additional 4,000-pound lift bag with them.

Once they threw that on there, giving them 14,000 pounds of lift, they were just barely able to lift the boiler. That means the Pretoria’s boiler weighs more than 13,000 pounds. In short, it’s massive.

“It was like we had run out of space,” explained Decker, “so we just left it there. We were hoping to secure it down, but we didn’t have the time that year.”

When they came back in 2017 to verify where the boiler was, it had moved again from where they had dropped it. This turned out to be a good thing since it had shifted to a better location. That’s where they ended up drilling down into the bedrock, putting in some bolts and tying it down with chains.

In fact, it ended up being right next to another section of the wreck that had not been documented—a part of the hull. This is about 75 feet to the north of the main wreck site.

“With a visibility of only about 30 feet, that’s a long way,” noted Decker.

They also found a door they think goes to the boiler—the fire door that would be opened to throw coal through to heat up the boiler. Decker and his team think it went down with the boiler when it was put back in 2001.

“There was one picture that kind of looks like the door is there,” described Decker, “so we’re pretty sure that was the door. It was somewhat flattened because we think the boiler had rolled over it. So we picked it up and moved it back to over where the boiler was.”

“Only a few people have seen this wreck since it went down, but not many,” shared Decker. “Then we found another missing section in 2018—a big section with the rudder on it. That was pretty exciting because no one had seen that.”

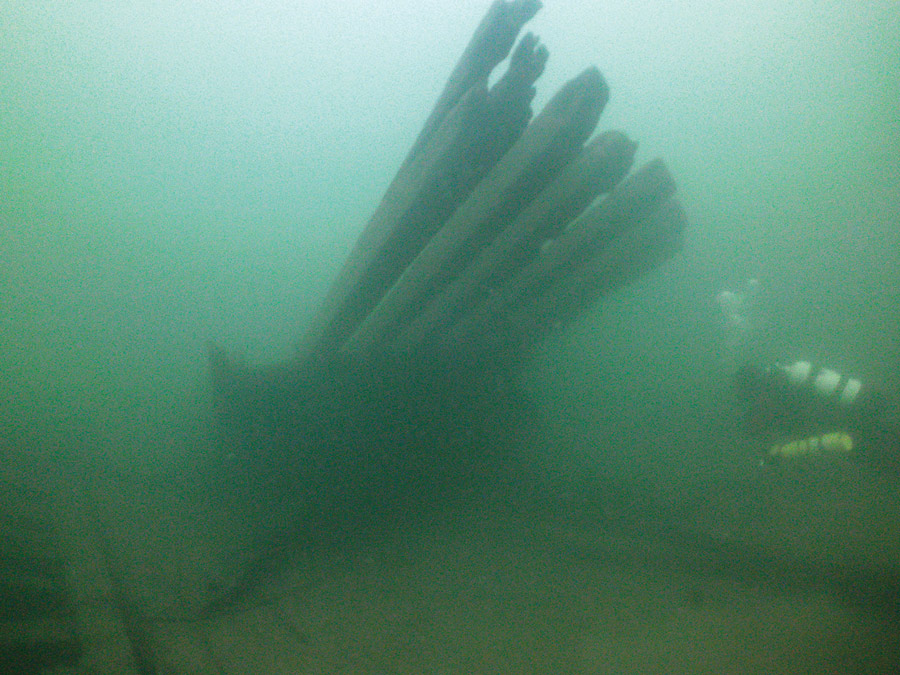

“As an engineer,” observed Decker, “one of the things I find so fascinating about this shipwreck is that drawings were not made of individual ship parts on the wooden ships—just a couple of cross sections of the entire ship. The ship builders just knew how to build and craft the parts. Some parts must come from a particular part of a particular tree. So we dive on the wooden ships to study how the builders actually built them. Once steel ships started to get built, more parts were individually drawn. Lake Superior, with its lack of zebra mussels, is the only Great Lake where the ships can be seen without the covering of mussels the other Great Lakes shipwrecks have.”

Decker and his team at GLSPS will continue to check on the wreck site every year to monitor it for deterioration and to see how the boiler’s tie downs are holding. They will continue to search for missing wreckage.

Decker is happy for the opportunity to keep diving the site since he finds it to be a fun and enjoyable trip. It’s also a relatively easy dive as it’s not hard to get to and it’s not too deep, the deepest point being around 60 feet and most of it being around 55 feet.

“It’s exciting,” added Decker. “It’s a big wreck site and it’s just really cool.”

Great Lakes Shipwreck Preservation Society wwwglsps.clubexpress.com